In this article I will share with you a recent 12-week cycling training journey that was designed to make me fitter, stronger, and faster on the bike than ever before. At the age of 41. In doing so, I will break down four major alterations I have made to a general approach to cycling including structured training, off-bike gym work, nutrition, and bike fit.

For each of these four topics that I break down below, I’ll be bringing in subject matter experts, including Ryan Thomas (RCA Head Coach) for structured cycling training, Aaron Turner (PHD in Load Management/High Performance Coach) for off-bike gym work, Steph Cronin (Sports Dietitian) for nutrition, and Neill Stanbury (Sports Physiotherapist & Bike Fitter) for the changes I made to my bike set-up.

But first of all, I need to clear the air. As I’ve had a lot of people ask me – why?

The Motivation

In July 2021, I turned 40 years of age.

Depending on who you speak with in the cycling world – which arguably has one of the largest age demographics of all the recreational sports that exist – I could either be ‘a young pup’ or ‘an old boy’.

But either way you flip this, if you look at the science on aging, you’ll quickly uncover that 40+ isn’t the same as 20+ nor 30+ from a raw physiological standpoint. For example, in men, testosterone is said to reduce by circa 1% per annum when you hit your early thirties. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

So, it comes as no surprise that the age factor, aka the ‘age excuse’, has really been ramping up like never before since I turned 40. Family, friends, and social media followers/subscribers – notably on my personal YouTube channel – have all gotten involved in the age excuse sentiment.

Although, it’s some of my same-age mates that seem to throw it around the most, using age as the reason why they can no longer ride at a certain pace or participate in a particular group ride.

Personally, I think it’s all bullshit.

I feel this way because I see first-hand on a week-to-week basis men and woman in their sixties hitting personal best (PB) power numbers, climbing a local hill (or mountain) faster than they’ve ever done so before, and/or finally getting around a local group ride that’s always been their nemesis.

I’ve also seen men well into their fifties at a local club racing level towelling up twenty-year-olds in the A grade criterium scene.

So don’t give me that age crap!

However, to be fair to those on the age excuse side…

The above examples I share are only anecdotal and not overly compelling at the same time. Not a great combo.

In other words, what if the sixty-plus-year-old I mentioned above had never done any structured training before? Then there’s some significant low hanging fruit for them to improve their performance, despite the age factor.

The criterium racer, well into his fifties…perhaps he has always been a super strong freak on the bike, which makes it hard to quantify how his specific age has anything to do with his ability to squash a few twenty-years-olds. Of course, there’s the race smarts factor too.

So, to prove a point about this age excuse phenomenon – which appears to ramp up significantly after the age of 40 – I thought I’d experiment on myself.

Can I definitively become faster than ever on the bike at the age of 41? Me now VS younger me, who’s been all over structured training since early 2014.

Which ponders the question – how could I prove this in a compelling manner?

*You can watch the entire experience unfold in the below 30min video...

Cycling And Power-to-weight

In cycling we have a metric called power-to-weight.

Power can be produced using several different methods on a road bike, but my preferred method is the pedal-based system.

For this experiment, I was using the Wahoo Powerlink Zero pedals. But I’m also personally a big fan of the Assioma pedal system. Both can be easily moved around from bike to bike, which makes life a lot easier.

So now that I have a power meter to register watts, what are we looking for?

Notably, how many watts I can produce over certain periods of time.

We could get caught down a rabbit hole here, as there are so many different time segments you could assess in an endurance sports setting. But thankfully, in road cycling, there are four critical time-based segments commonly isolated because of their correlation with physiological assets.

They include:

- 5 seconds – Neuromuscular effort

- 1 minute – Anaerobic effort

- 5 minutes – V02 Max effort

- 20 minutes – Threshold effort

The beauty of these four time-based segments is that we can also compare ourselves with the general population via this spreadsheet put together by Hunter Allen from Peaks Coaching, who co-authored the famous book Training and Racing with a Power Meter.

So that’s the power side of the equation.

The weight side is simple…

How much do I weigh in kilograms? Then divide that weight by the power segments.

So, for example, if I weighed 70 kilograms and could produce 1000 watts for 5 seconds, my 5-second neuromuscular power-to-weight number would be 70/1000, or 14.3 watts per kilogram.

How you sit on the bike and your overall aerodynamics will obviously impact raw speed. However, this power-to-weight number should correlate nicely with how fast you are on a bike. That is why professional cycling teams have been known to pick up riders purely on the raw power-to-weight numbers. Then the ‘race craft’ is trained into them.

My Power-to-weight History

I have been road cycling since 2008/2009.

Given the price of power meters and me spending a few years figuring everything out, it was 2012 when I purchased my first ever power meter. Being in a corporate job at the time and earning some good dollars, I didn’t hold back either. I purchased a Quarq-based system for just under $2,000 Australian.

Thus, my power-to-weight numbers go back about 11 years. I would have been 30, turning 31, when I bought the Quarq.

In terms of my body weight – if I’m to be honest with you here – I have never intimately tracked that week to week or month to month.

However, what I do categorically know is that my lowest of the low weight back in my thirties was 77 KG. In fact, it was probably more like 77.2 KG. I never cracked that magic 76-point-something.

Thus, I have used that lowest bodyweight to come up with my all-time best power-to-weight numbers across the four segments mentioned above.

What you will note above is that all my previous best numbers were in that 2014–2016 era, which didn’t surprise me when I was researching the data earlier this year.

Why?

During that era I was racing in Melbourne with an amateur cycling team called InForm Racing, and thus, training to structure consistently. I was completing about 10–12 hours per week on the bike with a coaching group in Melbourne called The HurtBox.

It was during this era, as well, where I was getting pushed to the extreme via racing in the local road and criterium scene. In fact, one of the goals of the team – when we first started – was to get all riders from B Grade into A Grade. This was a bigger step than I could have ever imagined, and it was during some of these A grade races that I created all-time PB power numbers.

The above graph is from an A Grade Glenvale criterium in January 2016. The average watts were 348, and normalised watts 372 for the hour. This one hurt, and it was during this race that I achieved a 20-minute power number PB of 381 watts. Coming in the middle third of the race, where I found myself in a breakaway with riders A LOT better than me!

This 20-minute example provides a representation of how my previous PB power numbers were achieved in races, by getting pushed to the extreme.

So how would I take my younger self on?

The Testing Protocol

Once I identified all my previous PB power numbers (across the four segments), I needed to come up with a plan of how I could take on my younger self.

In Melbourne – a city of almost five million people that’s regarded as Australia’s cycling mecca – I had the luxury of going to races on a weekly basis and riding against elite riders that had professional aspirations, sometimes even racing professionals who were back for the off-season in December /January. You can see a pic below of me rubbing shoulders with Australian great Simon Gerrans.

Now living in the small community of the Noosa Shire, Sunshine Coast, Queensland, I do not have the same opportunity. Yes, the local Brisbane scene is strong, but spending close to four hours in the car every Saturday morning to race for an hour? No, thank you.

So I sat down with my coach, Ryan Thomas, and we came up with a plan on how I would aim to target these four power-to-weight segments at age 41.

Over two days – at the start of my 12-week training plan and at the very end – I would do the following:

- Day One – test the 5 second sprint x 3 attempts and the 1-minute effort x 1 attempt

- Day Two – test the 5 minute and 20-minute effort, following the official 20-minute functional threshold power (FTP) protocol.

For the 5 second sprint tests, I went to a local, closed road criterium track; for the one minute test, I used this one minute climb; for the 5 minute test, I used this closed road climb; and for the 20 minute test, I used the same closed road climb into a undulating loop called Dath Henderson Lap.

Whether I had the advantage now, at the age of 41 – picking the above segments and chasing a number on a screen – or at the age of 33/34 – racing in extreme Melbourne conditions – I’ll leave that for you to decide. However, please know that the power segments I chose were done out of convenience and practicality, more than anything, with my 20-minute test being a prime example of not being favourable (terrain wise).

However, despite my original plan to hang my hat on these power segments as evidence that I can be faster on the bike than ever at the age of 41, it’s some old race data VS new race data that I’m going to hang my hat on. Thankfully, I did manage to get down to Brisbane for a BIG road race during this training block, making for a nice comparison with an A target event I had in 2015 when racing with InForm.

But more on that later…

My Starting Ground

So, to get the ball rolling, I went and tested all four segments in January 2023. This was designed to give me a sense on whether I had a chance, or was I dreaming that I could take on my younger self?

Additionally, what improvements could I make in a 12-week period? Albeit, I had been loosely training to structure and doing a fair amount of intense work leading up to beginning this plan.

Thankfully, I wasn’t overly far away from my previous PB numbers, and I actually personally bested my one-minute segment.

Although to be fair, this one-minute segment was the sole segment where I do feel like I did have an advantage at 41.

Why?

The hill that I used for the test is borderline perfect for an all-out one-minute effort. The gradient isn’t overly steep, but steep enough to get out of the saddle and leverage the entire body. Additionally, back in the day, I don’t recall smashing up a hill that was exactly one minute in length. So, it’s a number I never really targeted.

On the other hand, the other three segments are a different story. I’ve done plenty of 20-minute FTP tests, my old benchmark 5-minute climb in Melbourne was Two Bays where I previously clocked a 442 watt power PB, and sprinting as hard as I can for 5 seconds? I’ve done that a thousand times.

But back to my starting ground…

As you can see from the table above, overall, I was reasonably close to all power PB segments. Some might even look at these numbers and say achieving victory against my old self was going to be a piece of cake.

However, keep in mind that I have been training or racing on and off for a 10 to 15-year period and I was still producing some decent 10 to 12-hour weeks on the bike leading into this 12-week training block. Bunch rides, HIIT training, base training, and the gym were included with my main issue being consistency.

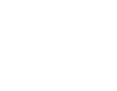

Above you can see my load chart in my training software, Today’s Plan. The length of the bars is demonstrating a chronic training load number (calculated using a 42-day rolling average ‘stress score’ given to each training ride) of around 50. Enough for me to ride the local bunches and stay relatively fit.

But if I’m to be taking on my old self and squeezing that extra 10–20 watts out of my top end, I knew I had to improve consistency and stick to a proper plan.

Setting Expectations

One of the big reasons why my load chart is all over the place is because my wife travels a lot for work. Generally, she can’t sit still either, always planning the next adventure for her or the family. This, in addition to running a small business and being very hands on with my kids, means that training consistently 10–12 hours per week becomes very challenging.

However, I have learned from the past to pick and choose your battles. Strategically.

So, in the middle of last year, I started to assess when it would be a good time for me to attempt this ‘Fast at 41’ project, as I needed a full 12 weeks.

Looking at the calendar, 2022 was a write off. So, I went into 2023 and saw that nothing was planned.

I sat down with the whole family during dinner time and explained that I wanted to train like I did back in the InForm days. While my kids probably didn’t give two hoots, it was ultimately directed at my wife! Do not go away for 12 weeks, was the subtle message.

Once the agreement was in place, I drilled it home on a weekly basis, so no one would forget. Once my wife was telling other people I had big plans to ride and train hard at the start of 2023 and nothing could be booked in, I knew the message had sunk into her brain and I was good to go.

Now keep in mind, I still split the kid duties with my wife 50/50 during this training period, but knowing when I would get outside and ride VS not having a predicable routine was the ultimate goal. And that is what I got!

Once Alice, my wife, was onboard, I needed to find myself a coach…

Why I Didn’t Self-Coach?

Back in the InForm days, I was coached for a couple of years. However, this form of coaching was more of a group on-road coaching environment. This was great motivation, meeting with others on the road during the same session, and an ideal learning environment to improve bunch riding skills. However, this coaching wasn’t overly specific to me as an individual.

Thus, I felt there was some low hanging fruit here.

Now, yes, I am a coach myself and therefore could have self-coached. But I felt deep down that I’ve most likely picked up some bad training habits over the years. I also wanted to have accountability to a program, especially if I was to truly follow a Periodised Plan, which involves progressive overload techniques, with strategic easier weeks to absorb physical stress, ultimately mitigating a fatigued state.

So, I hit up the RCA’s Head Coach (Ryan Thomas) to become my personal coach for 12 weeks. There were a couple of rules involved:

One – no more than 10–12 hours per week. This creates a level playing field with my old self and I simply didn’t have any more time available.

Two – a schedule that included alternating between indoor and outdoor riding. Indoor for the days I had the kids and outdoors being when it was ‘my morning’ to get out and be free.

Thus, most indoor sessions were around 50mins to 1hr in length and outdoor sessions were around 2 hours excluding Saturdays where I had more freedom to ride for long sessions.

Change One – Sustained Efforts

Often a plan will start with a period of base training. Depending on fitness levels, it could vary from 4 weeks to 12–16 weeks.

Typically, this phase is focused on Zone Two riding which is designed to boost aerobic fitness adaptations. However, in my case, being a fair old Zone Two junkie, my aerobic fitness was reasonable before we started this training block. Meaning, I could get straight into intensity.

Therein lies the bad training habit I thought I might have…

In the past, when I have self-coached for specific events, I would typically go straight for the jugular, heading to my local 1 to 2-minute hill climb for hill repeats, a 10km loop I do for low cadence threshold work, and the local criterium track for some all-out sprints. I’d progressively make these workouts harder as the weeks went by, sprinkling in some Zone Two and recovery work on either side of these HIIT workouts.

The problem with this? Or should I say problems?

The hill repeats workout I would do touches on VO2 Max and Anaerobic Capacity. Two upper end zones of training. Not to mention, I would often do these at a low cadence, which works more of the muscular skeletal system.

I’d also complete the threshold session using a combination of high and low cadence, depending on the terrain.

Finally, a sprint session at the track would either be after the Threshold session or done separately. Either way, that’s working another top end system, the neuromuscular system.

Ultimately, this is all upper end work that adds high volumes of fatigue to the system.

Starting this style of training too early means you can peak too early and/or end up in a fatigued state. In other words, this type of training has a faster shelf life than below-threshold forms of training.

The other major issue with my old approach to training was – because of this upper end focus – I neglected doing work between Zone Two and Threshold.

Zone Three/Tempo and Sub Threshold/Sweet Spot were essentially neglected.

If you haven’t heard of Sweet Spot training before, it’s roughly 88–94% of your FTP and is designed to enhance aerobic fitness adaptations established largely from Zone Two work. It’s not overly fatiguing either, meaning you can do more of this training without having to worry about the type of burnout VO2 Max work and above can bring on.

So, the program Ryan built out for me started with a focus on below-threshold work with one to two sessions per week around Tempo and Sweet Spot. Effort ranges started around 10–12 mins in length, building up to about 20 mins, with typically around 3–4 sets per interval and 3–5 mins rest in between.

I’ve done this style of training before, but it’s been more sporadic, i.e. I’m jumping on the indoor trainer and selecting a Wahoo SYSTM workout that suits my present mood. However, these workouts were always few and far between, meaning I quite possibly have never truly established upper end aerobic fitness levels.

Ryan wedged base training and recovery rides, with a once-a-week bunch ride, in between these sustained effort workouts. The Saturday bunch ride was left in the program because it’s what I like to do. Fun still needed to be part of the program!

The Saturday bunch ride also gave me some upper end work during each week. This meant I was still doing VO2 Max and above work on the bike via bunch rides consistently throughout the program. However, I wasn’t strategically doing VO2 Max and above training until the very back end of my program: Week Eight of my twelve. In other words, a major shift in approach from my previous training methods.

*Enjoying this read? Be sure to join the RCA’s weekly email Newsletter (green button below)

Change Two – Fasted Intense Rides Out the Window

The one aspect to cycling performance and aging that I can’t deny is a metabolism that seems to be slowing down.

In my thirties, I would go through phases of cycling, typically driven by life disruptions such as changing jobs, moving house, getting married, or having a newborn. These ups and downs in my training would often leave me with ups and downs in my weight. In other words, my diet pretty much stayed the same, but if I was training more, I’d simply lose weight and get leaner. I still had to use self-discipline during that 2014/15 era to lose that final 1 KG of body fat for racing, but ultimately, I could get fairly lean just by increasing my training load.

In the last few years, however, I’ve noticed that the extra weight I carry when I’m not focused on cycling doesn’t tend to leave as quickly (if not at all) when I ramp up my training load. In other words, I have noticed my metabolism slowing down.

In order to take on my younger self, I thought I’d leverage another RCA asset, our resident Sports Dietitain partner, Steph Cronin.

It’s interesting when I ponder all the sit-down interviews I’ve had with Steph for YouTube content over the years; the number of times I’ve heard her discuss scientifically backed carbohydrate intake for improved performance (*see study below) on the bike and not implemented it myself is staggering.

I guess you could say I’ve been old school when it comes to nutrition. Adding into the fold a fasting phase I went through, I’ve essentially conditioned myself to not want food in the mornings.

Enter fasted rides…

For all intense training sessions during the week, I’d never eaten or consumed anything before or during the session for years (outside of the morning black coffee). Let’s just say I didn’t like the feeling of food digesting, or sweet carbohydrates in the morning. Even my bottles were filled with plain water.

The only time I’d ever consume something was for the longer Saturday ride, and I did this in order to not bonk. In other words, my nutrition strategy was all about avoiding the bonk.

Post session, I’d often make a smoothie with some protein powder, thinking that was replenishing enough.

Moving into lunchtime, because my days are often cut short because of school pickups or the kids getting home around 3pm, I rush lunch to keep working. Content creation requires a lot of focus time after all.

Then, at some point mid to late afternoon, I would UNLEASH, devouring crackers, crisps, dark chocolate, whatever I could find in the pantry or fridge. This gorging episode would then normally go into dinner time – where I’d fill my plate up a couple of times – and even post-dinner snacking was a real problem.

In other words, I was backloading my day.

External to being a terrible strategy for losing weight and getting lean, what I didn’t realise until recently is that this strategy was impacting my training performance, notably an ability to train at a high level consistently and my general recovery.

So arguably the biggest focus Steph had for me was ‘sandwiching’ my sessions with more fuel, notably carbohydrates.

Interestingly, the first 2–3 sessions where I ate breakfast prior to the session, I struggled with my gut. I could feel the food – which was either banana on peanut butter toast with honey, or muesli – digesting. I didn’t like it, and perhaps this is another reason why I’d refrained from eating prior to a session in the past.

However, like anything, the gut (and brain) needs to be trained, and I eventually became used to this over the course of a month. I also became a lot better at consuming on the bike, whether that be liquids (Infinite has become my fuel of choice), oat bars (Koja being my favourite), and even gels for the super intense sessions.

Then, after any hard, long session, I’d grab a salmon bagel from my local coffee shop and still have the smoothie when I got home.

For some icing on the cake, I started to prep lunch on Sundays, meaning I could still technically be quick with a lunch stop and not lose work time. As result of this prep strategy, lunch became a lot healthier and more substantial, typically, being a chicken veggie mix that I’d add to two wraps.

As a result of ‘sandwiching’ my sessions with carbs and a decent hit of protein (which is a macro-nutrient that makes you feel fuller), my afternoon cravings died.

In addition, I wasn’t overly hungry at dinner, and post-dinner snacking became a row of dark chocolate. And that was it.

Outside of the performance gains in training and a much better recovery day to day, two major callouts come to mind with this nutritional transformation. See skin fold numbers here (and also my food dairy if you want to check that out)

One – I am not calorie counting. In fact, if anything, I am eating more than previously. I’ve just flipped the way I consume and ensure I strategically add protein to all meals (external to the pre-ride meal which is carb focused).

Two – This is the first time in my cycling history where I haven’t had to really try hard to get lean. In fact, 76 KG, which is where I ended, is the lightest I’ve ever been. In the past, during the 2014/15 era, 77KG was my lightest and I really felt like I needed to use self-discipline to get there.

As a result of the above, the work I’ve done with Steph feels like it’s not just a ‘get fit for cycling’ thing. It’s an approach to general consumption that I’ve changed for good.

*You can watch the entire nutrition experience (with Steph Cronin) unfold in the video below...

Change Three – The Weightlifting Dilemma

Ever since my dad took me to the gym way back in the mid-nineties, I’ve been hooked on doing weights. Watching Pumping Iron with Arnold Schwarzenegger ten times certainly added fuel to my teenage fire, motivating me to be consistent with the gym all throughout my teenage years and well into my twenties.

In fact, my upper body was so well developed as a schoolboy that some of the rival rowing schools speculated I was on steroids. I can promise you; I wasn’t!

However, by the time I’d hit my late-twenties I was looking for something different.

Enter, triathlons… which led me to road cycling shortly afterwards.

However, despite this shift in physical activity interest, I’ve always maintained that one gym session per week. I do still enjoy the physical sensation of lifting weights and I appreciate the benefits. I also physically like having some upper body, despite the fact it doesn’t go well with cycling.

One major aspect to the gym that I’ve noticed over the years, especially as I’ve brought more legs and core into the fold since starting cycling, is delayed onsite muscle fatigue (DOMS), the muscle soreness you can get 24–48 hours after a session.

This creates quite the dilemma if you’re in an intensive block of cycling training, where most weeks you’re aiming for three intense bike sessions per week. If you want to have a recovery or aerobic day after an intense training session on the bike, where does the gym workout fit in? Especially if you’re going to be sore for the two days that follow.

So once again, I leveraged another RCA asset, our resident Strength and Conditioning Coach (who has a PHD in load management), Aaron Turner.

I took Aaron to the gym and showed him what I was doing. He quickly identified me as a circuit guy since I go from one exercise to the next, working different muscle groups across three different exercises, before I move to the next three. I don’t really stop, and the exercises are all over the place.

This circuit strategy came with three big issues, which Aaron was able to quickly rectify.

One – as part of my circuit strategy I was bringing upper body work into the front section of my workouts. This goes against the principles of the priority model (see study below) where I should be frontloading my workout with the most important exercises, which for me involve the legs. Thus, Aaron’s advice moving forward was to put all leg work at the front of my gym workouts with abs in the middle and all upper body work at the end.

Two – Going close to failure on exercises was the main culprit for my dreaded DOMS. For most exercises I was also doing too many reps, typically around the 8–10 mark. So based on research (see study below), Aaron suggested aiming for a weight where I can do seven reps maximum, but only lifting 4–5 reps of that weight. This still achieves the strength outcomes I’m aiming for with the gym, without causing additional fatigue that could disrupt the cycling sessions.

Three – My previous circuit style training added unwanted fatigue in the gym. I get enough aerobic and anaerobic work on the bike, so Aaron suggested I spend at least 2–3 mins resting between each set. Then, if I’m desperate for circuit mode, I can bring that into the upper body work after the leg exercises.

Whether this approach has improved my bike strength, I can’t really say. Perhaps it’s too early to be the judge, as ultimately, I was already a number of weeks deep into my 12-week plan before I saw Aaron.

What I can categorically say though is that I‘m no longer getting DOMS, meaning I have a lot more flexibility where I can place gym workouts.

Obviously placing the gym away from any intense session on the bike is best, but when you have a crazy busy life/work schedule, I often fit the gym in wherever I can squeeze it.

*You can watch the gym session (with Aaron Turner) unfold in the video below...

More Power with 165 MM Cranks

In March 2020, I walked into Neill Stanbury’s bike fitting studio in Brisbane without realising this meet and greet would be the beginning of a friendship and business relationship, as well as a complete transformation in my bike fit.

You can watch Neill’s original bike fit with me here, but there was one suggestion Neill made during that discussion, which we didn’t change on the day (because of cost and product availability). That was changing from 172.5mm cranks, which I’d been on all my cycling career, to 165mm cranks.

Why?

Outside of the general right-sided hip pain I’ve always had, Neill identified that I had a hip impingement, which is basically where the ball and socket of the hip don’t get along.

Notably, I have trouble raising my knee to the height 172.5mm cranks demand and that keeps my pelvis more upright. Not great for general comfort on the bike, nor aerodynamics.

So many months after my first rendezvous with Neill, I took the leap of faith and transitioned to 165mm cranks.

Surprisingly, at only 7.5mm difference, I immediately felt more comfortable on the bike with the ability to roll my pelvis forward and more easily ride in a deeply flexed position. Golden!

Shortly after this crank length change, work/bike review commitments got in the way, and I was back on the 172.5 mm cranks for a good 18–24 months.

However, knowing the benefit of this 7.5mm change, I was eager to revert at some point in time, with this training series proving to be the compelling event.

Outside of a bike seat rabbit hole that this crank length change left me with (again!), I immediately felt better on the bike, ready to tackle my 12-week HIIT plan without right sided hip pain and generally feeling more at one with the bike.

During the crank length swap-over session earlier this year, Neill proposed a challenge to me.

He suggested that the shorter cranks would enable me to produce more consistent top end power for longer, because there is less contractile effort required from the muscles due to a higher cadence.

Challenge accepted!

As you can see from the stats below, I did my initial testing on the 172.5mm cranks and the final testing on 165mm cranks.

Of course, I was fitter at the end of the process, but as Coach Ryan said in my concluding video, there’s not a huge amount of improvement you can make in a one-minute effort in a conditioned rider. It’s more about repeatability. So, I feel there’s a fair amount of meat on the bone when looking at the above one-minute comparisons.

*Watch expert bike fitter Neill Stanbury explain the reasons behind 165mm cranks

So, am I Faster at 41?

Never in my life have I been so nervous for testing.

Outside of the fact I’d told at least a hundred thousand people about this goal (via YouTube content), this journey inadvertently became a taste of my own medicine.

In other words, if I was to fail here – whether that be not hitting power PB’s or perhaps not even improving from the starting point tests – things would not look good on me, nor on the RCA.

So, on the 1st and 2nd of May 2023, after some terrible nights’ sleep with extremely nervous, tense energy, I went and completed the four tests.

See results below:

As you can see, the 5-second sprint test is the only number I missed, and thankfully, it was the segment I wanted the least.

I still wanted it, don’t get me wrong, but I have never been a sprinter and will never take a sprinting strategy into any event or race. I’m always going for a breakaway or an attempt to ride off the front near the end! So, it was the 5-minute and the 20-minute I wanted the most.

The anomaly you can see in the final testing is an additional 20-minute test, roughly one week after the official testing.

Why did I do this?

Reflecting on our testing protocol for the 20-minute effort, we definitely had this one wrong.

While we used the official 20-minute testing protocol to gain an accurate FTP number, the 5-minute effort prior to the 20-minute leaves a lasting level of fatigue. This meant there was an unfair advantage to my younger self, who raced that criterium in January 2016 on fresh legs.

Thus, eight days later, I went back to the same terrain on fresh legs and had another go, achieving an all-time PB number of 384 watts for 20 minutes.

In other words, my 41-year-old-self had personally bested three out of my four critical time-based power segments for cycling, at an all-time low weight of 76KGs.

However, I don’t personally feel this is the most compelling piece of data I have to share with you, even though I started this entire process with the goal of hanging my hat on these numbers.

As mentioned above, it’s some race data that I feel tells the real story: old VS new.

See below race data from:

I chose the Tour of Bright (Stage Two) 2015 because it compared nicely to the Tour de Brisbane 2023 for three reasons:

- Both are road races around three hours in length.

- I was in a breakaway during both races for around one hour leading into the final stages.

- Both had hard finishes which included long hills.

Now yes, I did complete a 19-minute time trail the day prior to Stage Two of the Tour of Bright in 2015. However, I was in peak form! I’d been training for the event for months, and a 19-minute effort in a time trial position should not be an influencing factor the following day, in my opinion. Especially when we trained for this sequence, and I was ‘just getting through’ the time trial. In other words, it wasn’t my forte.

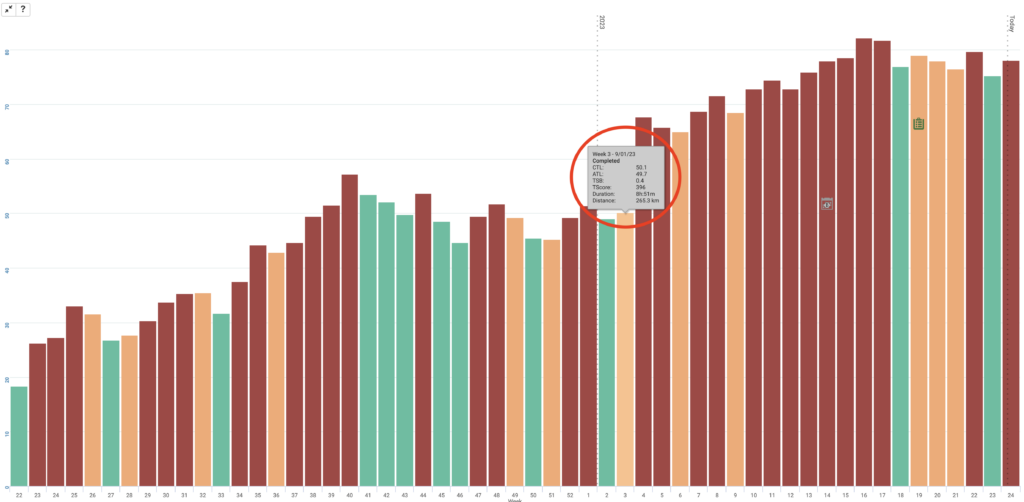

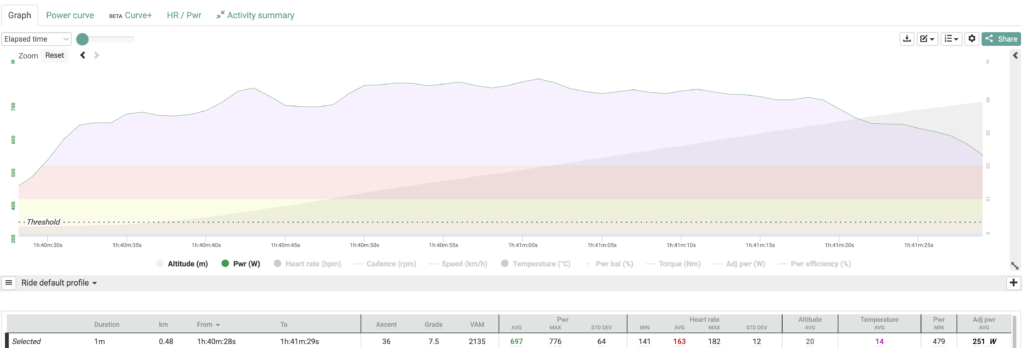

External to the average power and normalised power being far greater for the Tour de Brisbane, the main area of focus I’d like to point to is the final section/sections of the event.

You will see at the Tour of Bright, up the final climb, I am struggling to ride at, or just below, threshold. Given the length of this climb of about 20 mins, I should be able to hold a threshold effort, especially considering that – after the 45-minute breakaway attempt – I had almost one hour to rest my legs in the bunch leading into the climb.

However, I am struggling to even maintain sub-threshold, often dipping into my tempo zone, particularly towards the end. In other words, I am fading away, big time.

And this fading out sequence was so very common back in the day.

If I was to speculate, now knowing what I know, I’d say this could be due to a combination of any of the below:

- Not fuelling properly before or during the race

- Not enough sustained efforts in training

- Too much upper end VO2 Max/Anaerobic work in training, leaving me fatigued

- Poor bike fit (172.5mm cranks?)

- Inadequate strength resources from a poor gym routine

Whatever it may be, the final stages of the Tour de Brisbane tell a different story. I rode into the final hill in a breakaway, at, or around threshold, for over one hour.

At the bottom of the hill my breakaway companion gets a cramp and I’m on my own. I remember riding up that 8 to 10-minute climb at a sustained VO2 Max effort (of circa 380 watts), thinking to myself ‘why haven’t I blown up yet’.

And I never did.

In fact, I was joined by one of Queensland’s top master riders at the top of the hill and rode to the finish line with him, swapping off at around threshold/V02 Max.

You don’t need to believe my words here, but I categorically know that the younger Cam would have blown up, for sure. I reckon within the first couple of minutes of the climb.

Whereas 41-year-old Cam, who’s become a lot smarter via the four changes above, rode strong to the end. No more Captain Fadeaway, and a rider I’d pick any day of the week VS his younger self.

So, you could conclude by saying this journey wasn’t so much about getting faster.

It was about getting smarter!

Interested in following a similar path over 12 weeks? You can apply for the RCA’s next intake below…

STUDY’s REFERENCED:

Nutrition targets for events and HIIT training: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6566225/

Priority model for Strength Training: https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Abstract/2006/02000/INFLUENCE_OF_EXERCISE_ORDER_IN_A.22.aspx

Avoiding hitting failure in gym exercises and strength gains: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-017-3725-7

My Strava Segments for the final testing:

The 20 min test on fresh legs within this ride: https://www.strava.com/activities/9042312332

The 5min into 20min test within this ride: https://www.strava.com/activities/8993479494

Sprints and the 1 min test within this https://www.strava.com/activities/8986972953