Incorporating rest and recovery into one’s cycling training is vital for improving performance, reducing the risks of overuse injury and the onset of fatigue. So, in this article, I will lay out the importance of rest and recovery as a cyclist, through scientifically backed evidence and understanding.

Before I delve into the science relating to the importance of rest and recovery as a cyclist, and to best appreciate the content of this article, you should practice some imagery through recalling back to your school days. In doing so, you will become equipped with the tools to conceptualise the importance of rest and recovery as a cyclist.

Now, if you are not sure what imagery is, or unsure how to perform imagery, here is a simple definition of mental imagery:

“Imagery can be defined as a mental skill that requires one to recall and mentally ‘relive’ past experiences of a scenario or a past event, thereby ‘recreating’ and ‘re-living’ that very same experience in one’s own mind”.

So, through the following steps, let’s practice imagery before we explore the importance of rest and recovery as a cyclist:

- Close your eyes and recall to the time you and your cycling buddy sat down at a café and ordered a coffee after successfully nailing the most brutal peak or climb of your ride

- Now, picture you with your cycling buddy, and your coffee topped with rich golden crema, placed on the table between the two of you

- Next, recall and imagine the aroma and steam, rising from the coffee that is placed between you and your cycling buddy

- Now, try to ‘smell’ that aroma

Well, no, the coffee does not exist in this present moment, but it is likely that you can ‘imagine’ and ‘smell’ the aroma of the freshly brewed espresso.

Now that you understand mental imagery, recall those long mathematics, English or science classes.

Again, shut your eyes and try to imagine attending school and sitting in the classroom with your teacher, for the same subject, and for the entire day.

I can guarantee that you would only acquire the information taught from the initial thirty to sixty minutes of that given class, and the remainder of the information absorbed would lack quality.

Yes, the teacher may have covered a large amount of content, but undoubtedly, you as a student would not have learnt effectively.

With this in mind, the current education system follows a framework where students are provided with short, mostly non-consecutive classes, spread throughout the week. This in turn, provides a break, and a stimulus to absorb the information taught, and to recommence the next session in a fresh state resulting in an accumulative learning experience [1].

Comparatively, cycling, and athletic training follows a similar rationale.

Meaning, for the human body to react to any physiological stresses of cycling training, rest is required for the body to repair damaged tissue, absorb the stresses of training, and consequently improve as an athlete [2].

“The fact is, the vast majority of recreational and amateur road cyclists hit a plateau. It could be anywhere between one to two years into their cycling journey. While anecdotal – from our experiences working with hundreds of recreational and amateur cyclists from all over the world – riding too hard, too often, is mostly the root cause of this ‘plateau’.

Logically, this makes sense too. You’re trying to make the most of your limited time to train, so you ride hard most of the time. But unfortunately, this strategy crescendos into a fatigued state, leaving you unable to really progress your cycling”.

Road Cycling Academy (RCA)

How the Body Responds to Cycling?

Resting as a cyclist is an important factor of one’s cycling training program. As such, with the development of scientific understanding over many years, sport scientists and strength & conditioning coaches are constantly experimenting and recognising new strategies to enhance performance [2].

One crucial field of research circulates around the notion of rest and recovery – and, finding the correct balance between intense training and recovery, to ensure cyclists and athletes do not ‘burn out’ [2].

In other words, when cyclists experience the stresses of training, the human body moves away from ‘homeostasis‘ [3]. Homeostasis, quite literally, refers to the human body remaining in a ‘single steady state’ [3].

Essentially, the human body constantly maintains its homeostasis whether or not one is cycling, to ensure the healthy functioning of the body through altering the regulation of the core body temperature, blood glucose concentration many more functions [3]. As such, all these functions are controlled by vital organs within the body [3].

Fundamentally, the body shifts away from a ‘resting’ homeostatic state to ensure the high efficiency of the cyclist, whilst simultaneously balancing homeostasis [3]. This in turn, places stress on the body as it is not in its ‘normal resting’ state [3].

Now, this leads us onto the ‘million-dollar question’.

How does Rest and Recovery Influence Your Cycling?

Quite simply, recovery can be understood as a period that is required to recommence exercise in a rested and recovered state [4]. Recovery or rest for cyclists can last from a few hours, to a full week, depending on the event or training [4]. And, during the recovery period, the body’s physiological systems re-fuel, repair and return the body back into resting homeostatic state [4].

Importantly, it is pivotal to understand that your hard training sessions or ‘HIIT’ workouts are not the sole cause of improved fitness as a cyclist [4]. In fact, the recovery period allows for the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems to absorb the stresses of training, and to respond by adapting to the stimulus for when you next get back onto the saddle [4].

In essence, recovery, and rest as a cyclist, is equally important to the training session [4]. Well, precisely, without recovery, the training can be deemed as ‘counterproductive’ [4].

Related: What is a Cycling Recovery Week?

Improved Cardiovascular Function at Rest

Upon immediate cessation of ‘large muscle’ exercise such as cycling or running, the human body enters a state of ‘post exercise hypotension’, commonly known as a reduction in blood pressure [4]. And, as you discovered earlier about homeostasis, the ‘post exercise hypotension’ will only take place during rest [5].

Yes, ‘post exercise hypotension’ is real, and that is why aerobic exercise can often be used as a ‘medicine’ to treat cardiovascular disease [5].

So, why is this important for cycling?

It is, and simply because ‘post exercise hypotension’ results in the heart pumping blood less forcibly around the body [5]. Meaning, the heart, or more specifically, the efficiency of the left ventricle improves, thereby placing less stress on the cardiovascular system and improving cardiac output [5].

In addition, the ‘post exercise hypotension’ can further allow for improved recovery of blood plasma volume after the cessation of cycling [5] – and what does this mean for cyclists?

Improved cardiac output, and long-term cardiovascular adaptations [5].

Furthermore, the ‘post exercise hypotension’ aids in adequate muscle recovery together with the ingestion of glycogen-based foods or drinks such as your common Gatorade, SIS Gel or even your good old Jelly Belly’s [4,6].

Essentially, when glycogen is consumed immediately following your cycling training or race, a short window of ‘glycogen uptake’ becomes available [6]. During this window of opportunity, the body goes through a process of amplified insulin sensitivity, which in turn promotes an increase in glycogen delivery to the muscles required for recovery [6].

Quite simply, when you train or race, you must rest to ensure the benefits ‘kick in’.

Now, this leads us onto the next section – how much recovery is beneficial to achieve the benefits of your cycling training?

General Adaptation Syndrome – Cycle Less, and Recover More

Wondering why you’re not getting fitter, faster, and better on the bike?

The chances you have been through such a period is likely. This is often the case for many beginner cyclists, as you begin to enjoy the thrill of cycling hard and fast – all the time, and every day.

Yet, as cyclists, we miraculously forget that recovery is equally important to training.

When it comes to high performance or strength & conditioning training, for example Usain Bolt, a track and field sprinter – will never train with the same gym-based power workout at 100% capacity on consecutive days. Put science aside, it simply will not yield any results.

Meaning, if Bolt was to train power in the gym at 100% capacity on Sunday, he will be fatigued on Monday. Consequently, if he was to perform the exact same workout on Monday, the fatigue will inhibit the ability for Bolt’s big and powerful legs to simply produce power with maximal force, and therefore will not stress the leg muscles at 100% capacity.

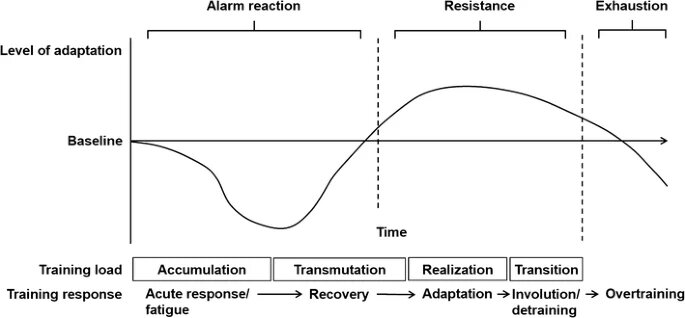

General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) is a theory that encompasses a three-stage process – Alarm Reaction, Resistance and Exhaustion [7]. Within the three-staged process, and through the correct programming, cyclists can reach greater heights than those who do not follow GAS.

Well, GAS essentially revolves around ‘homeostasis’ and the manner the human body responds to stress and adjusts its homeostatic state accordingly [7].

1. Alarm Reaction

The body undergoes physiological stress to the training stimulus, and as a result, enters a period of decline that is below baseline performance [7]. However, with adequate rest and recovery, the physiological systems react to the given stimulus and begin to ‘repair’ itself.

2. Resistance

As the body recovers, an increase in physiological performance takes place beyond baseline, such as cardiovascular or muscular adaptations. In the resistance stage, the body can respond to stimulus beyond the initial baseline performance.

3. Exhaustion

Too much stress on the body caused by various factors such as overtraining or even inadequate sleep, result in exhaustion, and cycling performance begins to decline.

Source: Adapted from [7]

Essentially, every cyclist should train within the Alarm Reaction and Resistance stages to ensure stresses of training do not lead to exhaustion, and through recovery, the exhaustion stage can be avoided [7].

Over time, as the body reacts to the stimulus for example, an 8-minute FTP effort, resistance is built, and as a cyclist, the training intensity can increase.

Anecdotally, the idea of GAS can be compared to your typical share on the stock market, which has ‘hi and low’ fluctuations [8]. However, upon recovery the overall growth and gains are likely to be greater than you ever imagined [8].

This idea of the GAS theory can further be explained by the ‘supercompensation’ theory. Subsequently, the concept of ‘supercompensation’ sheds light on the effect of training load and recovery [9]. As such, there is no specific amount of recovery, as the idea of supercompensation correlates training load together with recovery [9].

Typically, the window for supercompensation occurs during the rest period following the alarm reaction phase as the body reacts to the training stimulus, lasting anywhere from 24-48 hours [9]. At this point, the body then enters supercompensation at approximately 36-72 hours post the initial training, whereby muscle force returns to its full capacity [9]. During the supercompensation phase, it is vital as a cyclist to train to more stimulus or stress [9]. Otherwise, following 3-7 days from the initial training stimulus, detraining occurs if the cyclist chooses not to provide his or her legs with a training stimulus [9].

However, in the event of fatigue or even a rest week, ensuring that detraining does not occur is important, and, through incorporating a short, yet an intense training session during the rest week, can mitigate the effects of detraining [9].

Realistically speaking, when cycling training stimulus and recovery is adequate, cycling performance and adaptations improve over time [7]. However, when below baseline training or overtraining is prescribed, detraining occurs [7]. Finally, when inadequate training loads are prescribed, cycling adaptation will either decline or not improve [7].

How to Recover as a Cyclist

Recovery as a cyclist can vary based on the needs of each individual cyclist. For example, following an extremely fatiguing training session, an appropriate recovery may involve a recovery ride, or simply a day off the bike and a visit to a local massage therapist. While, for another cyclist the recovery process may involve an exercise walk and a yoga or stretching session to relieve the tight muscles.

The beauty about recovery is that there are no specific blanket rules regarding the recovery process. Rather, the recovery is about finding what process suits you as a cyclist best. For example, sometimes going for a recovery walk with a friend, can mentally refresh you as cyclist, while physiological recovery takes place. In turn, you may not only get back onto the bike physically stronger, rather mentally stronger, along with a better state of mind to smash out your next training session.

Now What?

I dare you to fight your very inner self and schedule some recovery or base rides during your training week. And yes, I can vouch for that feeling of trying to smash out some big rides on a sparkling sunny day. But, as you have discovered, rest and recovery are equally important to your cycling training. Not only is recovery important to battle fatigue, nonetheless it opens the window of opportunity for supercompensation that wondrously improves performance. Lastly, here’s a tip for your recovery days shh…ride easy on your recovery days, but to keep your motivation up high in the sky, try nailing a short Strava KOM that is no longer than 2 minutes in duration, and then return to your recovery ride. Ride Hard, Recover Harder!

References:

[1] G. Blasche, B. Szabo, M. Wagner‐Menghin, C. Ekmekcioglu, and E. Gollner, “Comparison of rest‐break interventions during a mentally demanding task,” Stress Health, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 629–638, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.1002/smi.2830.

[2] O. Dupuy, W. Douzi, D. Theurot, L. Bosquet, and B. Dugué, “An Evidence-Based Approach for Choosing Post-exercise Recovery Techniques to Reduce Markers of Muscle Damage, Soreness, Fatigue, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis,” Front Physiol, vol. 9, p. 403, Apr. 2018, doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00403.

[3] H. Modell, W. Cliff, J. Michael, J. McFarland, M. P. Wenderoth, and A. Wright, “A physiologist’s view of homeostasis,” Adv Physiol Educ, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 259–266, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1152/advan.00107.2015.

[4] S. A. Romero, C. T. Minson, and J. R. Halliwill, “The cardiovascular system after exercise,” J Appl Physiol (1985), vol. 122, no. 4, pp. 925–932, Apr. 2017, doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00802.2016.

[5] J. R. Halliwill, “Mechanisms and Clinical Implications of Post-exercise Hypotension in Humans,” Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 65–70, Apr. 2001.

[6] J. L. Ivy, “Regulation of Muscle Glycogen Repletion, Muscle Protein Synthesis and Repair Following Exercise,” J Sports Sci Med, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 131–138, Sep. 2004.

[7] A. J. Cunanan et al., “The General Adaptation Syndrome: A Foundation for the Concept of Periodization,” Sports Med, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 787–797, Apr. 2018, doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0855-3.

[8] E. Drinkwater, Seminar, Topic: “Periodisation” HSE331, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Deakin University, Melbourne, Vic, Jul. 2021

[9] T. Mitsumune and E. Kayashima, “Possibility of Delay in the Super-Compensation Phase due to Aging in Jump Practice,” Asian J Sports Med, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 295–300, Dec. 2013.

good stuff, I loved that you put the references for the arguments ❤️ quick question about the photo you posted with the girl foam rolling: I see *a lot* of disagreement between specialists on the topic “foam rolling the ITB”, with most of them saying it is pointless since that’s a rigid segment and we would be better off rolling the glutes and TFL. What’s the deal?

Hi,

Thanks for the feedback, and I am glad you enjoyed the article.

There is lots of research on foam rolling (FR). FR can be used as a method of self massage.

Unfortunately, I cannot provide an answer to your question, as it is beyond my scope currently.

Cheers,

Ari

Great article, thanks.

Hi Mark,

Appreciate the feedback.

Cheers,

Ari