Cleat position for cycling is often an unrecognised contact point on the bike, so in this article, I will outline three different cleat locations that are central for improved power, comfort, and injury prevention on the bike. The three focal points in this article will involve the lateral positioning, fore & aft and the rotational positioning of the cleats. Parallel to each cleat position, I will present the key anatomical and biomechanical reasoning behind each cleat location. Accordingly, once I have presented the importance of cleat positioning from an anatomical perspective, I will provide practical recommendations on the correct setup of cleat locations that would best suit the needs of cyclists at any level, experience, strength and fitness.

Why is the cleat position relevant to you?

Perhaps you have spent several hundred dollars on different saddles, pedals or knicks, yet you still feel uncomfortable on the bike. Or, maybe you are sensing that your muscles are not engaging well during a pedal stroke and believe it may be the root cause of a loss of power.

Does this sound like you?

Fortunately, some of the most complex discomforts on the bike can be solved through one notion – cleat position.

The Solution

The solution involves a simple formula:

Comfort and power on the bike is the product of anatomical structures of the human body corresponding to the contact points on the bike – pedals, saddle and the handlebars.

Let’s now understand how the human body functions:

The human body is comprised of many different bones that interact with each other through connecting joints, tissues and muscles. This interaction is referred to as the kinetic chain. When one joint is moved, it will interact with a connecting nearby bone or joint.

For example, standing up from a chair requires the legs to power the movement; however, the foot plays the most crucial role in stabilising the legs.

Essentially, the foot can be viewed as the ‘brain’ of the lower extremity of the musculoskeletal system – it is the base of support. A stable foot results in improved balance, stability, strength and power. Improved balance and stability allows for a more efficient power transfer from the gluteal, hamstrings and quadriceps, through to the pedals.

Applying the same theory to cycling, would it not make perfect sense to optimise cleat position? After all, we all want more power and comfort.

So how can you optimise cleat position?

The answer to optimising cleat position is to recognize that the human body is an asymmetrical being, whereas the bike is an entirely symmetrical product manufactured in a factory.

Putting this into perspective, recall the time you were shoe shopping and discovered that either your left or right foot was of a different size or fit. Did you end up purchasing the shoes? The likely answer would be yes, “with an insole in one shoe”.

Now, let’s apply this theory to cleat position.

Cleat position would be entirely different for all riders, given everyone is unique. Too often, cyclists adjust their cleats onto their shoes without understanding how, why, and where to place them. As such, incorrect cleat position is not only going to reduce comfort and power output, rather the likelihood of injury is increased.

“There are three key cleat positions that would highly benefit riders of all sorts”

Cleat Position 1:

- Lateral positioning – How comfort and efficiency can be improved with lateral positioning

Cleat Position 2:

- Rotation (Float) – The amount of cleat rotation

Cleat Position 3:

- Fore and aft – How fore and aft can impact power and comfort

Lateral Positioning

The Latin meaning behind the word ‘lateral’ refers to an object belonging to the ‘side’. In kinematics and anatomy, the word ‘lateral’ is employed to describe the positioning of a bone, muscle or tissue to a given side of the body.

As we have established above that every human has a unique physique, ideally a custom-made bike would ensure a correct fit.

However, a custom fit is uncommon, given its costly production and the broad adjustability that can be made on a stock bike to ensure the correct fit.

Assuming the bike reach and stack are ideal, cleat positioning can easily be adjusted to suit one’s physique. That is lateral positioning of the cleat. Lateral positioning of the cleats allows for the adjustability of the Q-Factor – the distance between cranks arms or the stance between both feet.

Given that bikes are symmetrical, and humans are asymmetrical, lateral positioning remains crucial to avoiding injury. Moreover, the bottom bracket size and structure are often the same across all bike sizes for any given manufacturer.

The ideal cycling position promotes comfort, endurance and power through the alignment of the femur head (top of the thigh bone), patella (knee) and the talocrural joint (ankle), in relation to the pedals.

In turn, a small-sized cyclist is likely to have a narrow pelvis and therefore alignment from the hip to the pedals is not possible given the Q-Factor is too large. Conversely, a large-sized cyclist with a wide pelvis is also likely to experience misalignment as the Q-Factor is too small.

Now, with the idea in mind that the Q-Factor must accommodate the physical needs of the cyclist, comparatively, it is the same to a railroad vehicle such as a train.

The train is an extremely efficient and smooth operating vehicle given its wheels are perfectly aligned with the tracks. This essentially allows for the train to operate smoothly without any disturbances.

Cycling is no different.

Correct alignment allows for the gluteals, hamstrings and quadriceps to execute their role most efficiently and naturally possible. Incorrect Q-Factor causes poor alignment and typically results in a very ‘choppy’ pedalling action. Common observations involve the knees rotated outwards for a larger cyclist or inwards for a smaller cyclist.

Importantly, knee and hip injury is likely to occur as the tibia (shinbone) and femur (thighbone) move in opposite planes.

Most shoe manufacturers accommodate minimal lateral positioning – approximately 2-3mm in each direction. Fortunately, many pedal systems allow for modifications if the lateral positioning has been exceeded on the shoes.

Companies such as Shimano offer a 4mm larger pedal spindle than standard to accommodate cyclists with a larger pelvic size.

Speedplay offers multiple spindle lengths that allow for all sorts of cyclists to choose the ideal length ranging from 50mm to 65mm.

Subsequently, the Q-Factor or stance can therefore be altered using various spindle lengths to suit the anatomy of the cyclist. Nonetheless, choosing the ideal spindle length involves ‘trial and error’ and the precise eye of a bike fitter who can assess the congruency of the hips with the pedals.

Thus, the lateral positioning stands as a crucial aspect of eliminating injury whilst improving power by allowing the anatomical makeup of the cyclist to pedal in his or her most natural movement planes.

Cleat Rotation (Float)

Cleat rotation is often referred to as ‘float’. Cleat float is the amount of movement the foot can rotate in the transverse plane.

Applying the same theory of the Q-Factor mentioned above, cleat float becomes the next important factor for improved comfort and injury prevention.

The amount of cleat float available depends on the type of cleat placed on the shoe. Shimano, for example, offers three types of cleats, thus float – Yellow (60), Blue (20) and Red (00).

The ‘Yellow’ option provides some movement, while the ‘Blue’ offers very little movement and the ‘Red’ does not allow any movement.

People often ‘think’ the ‘Red’ cleat allows them to “feel part of the bike and a cleat with float results in a power loss”.

However, this can have some massive ramifications.

Now, assuming the correct Q-Factor has been determined, the correct cleat float must allow for the hip, knee and ankle joints to interact with each other in the most natural manner possible. That means, if one’s natural tendency is to pronate (rotate outwards), or to supinate (rotate inwards) the foot, cleat position must accommodate such tendencies.

As such, the most sensible cleat float would be the ‘Yellow’ option. In turn, a cleat that allows some degree of float promotes the foot to mechanically operate in the comfortable plane.

Consequently, positioning the ‘Yellow’ cleat neutrally on the shoe allows for the float to accommodate either pronation or supination.

When the cleat does not allow for the limbs to move naturally, such as slight pivoting of knee or ankle, the likelihood of injury is increased. Additionally, as asymmetry or muscle tightness is likely to develop, cleat float allows for the micro changes within the body without compromising the biomechanical function of the joints.

However, if one can achieve the exact cleat angle relative to the amount of pronation or supination, cleat float can be changed to a lesser degree. This is often the case for elite cyclists such as sprinters.

Yet, for most and even professional cyclists, the ‘Yellow’ cleat option provides more than optimal foot support if their bike, shoes, cleats and saddle height are suitable.

Essentially, if one can pedal efficiently, cleat float does not impact power as the foot ‘should’ remain stable on the pedal.

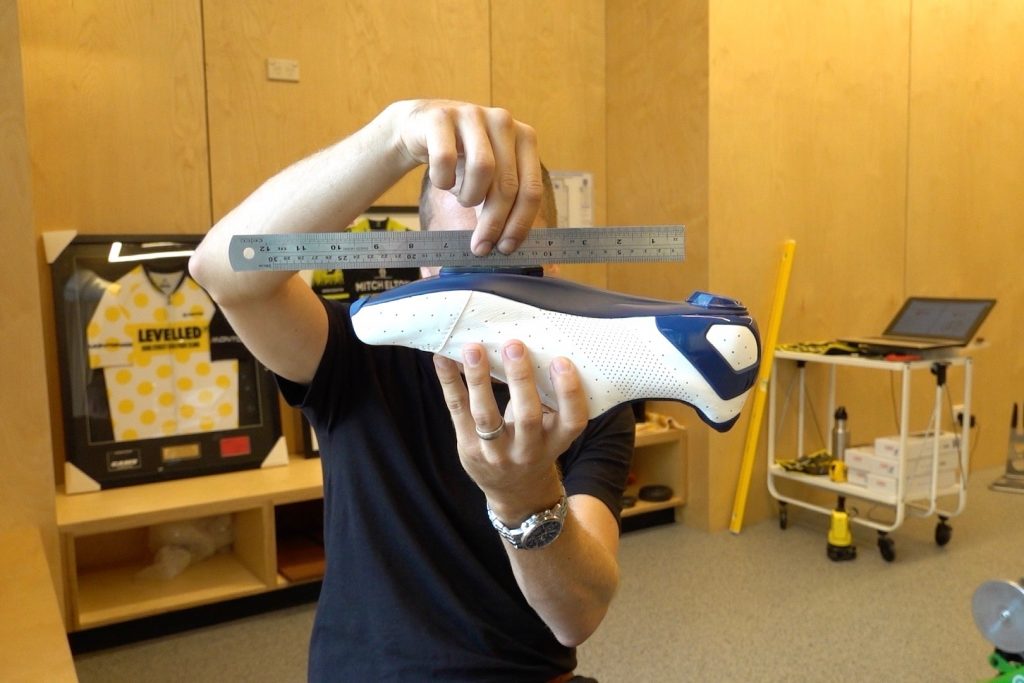

Fore and Aft

Fore and aft cleat position refers to the rearward and forward placement of the cleat in relation to the foot.

Fore, refers to the front half of the shoe, and aft refers to the back half of the shoe.

Traditionally, the theory of Ball Of Foot Over Pedal Axle (BOFOPA) explains that cleat position should be placed over the largest contact area of the front of the foot, the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint – the big toe.

The BOFOPA theory seems to have been transferred from running biomechanics, in which it makes perfect sense for the large toe to maintain ground contact during a running stride, where the toe can forcibly propel the foot forwards. However, regarding cycling biomechanics, the metatarsophalangeal joints do not produce any propelling forces and therefore operate differently.

Given the pedal is an unstable contact point on the bike, finding the correct fore-aft position can allow for increased stability of the foot.

In the case of BOFOPA, foot stability is not always apparent in some individuals, in turn leading to a decrease in power output and utilisation of the incorrect muscle groups. This is large since the pedal axle is the fulcrum that supports the foot, and an extreme fore cleat position unbalances the foot over the fulcrum.

In turn, placing the cleat towards the midfoot can allow for the foot be entirely supported by the pedal axle.

Placing the cleat towards the middle of the foot improves the stability of the foot during times of fatigue when quality movement patterns can no longer be sustained. As a natural response during hard efforts, most cyclists are likely to drop their heels. Consequently, a cyclist who is naturally a ‘heel dropper’ will only experience exacerbated heel dropping during intense efforts.

When heel dropping occurs, the natural response of the human body is to provide compensatory movement patterns, often involving a drop in the pelvis. This, in turn, leads to pelvic misalignment on and off the bike. Not only will it result in a non-efficient pedalling action, but it is also likely to cause injury to the hip, knees and lower back.

Placing the cleat midfoot allows all the large muscle groups to employ their efforts in the most efficient manner possible.

A midfoot cleat position reduces the effort exerted by the calf musculature as the foot becomes more stable. When the cleat is set towards the forefoot, the natural tendency of the human body is to become quadricep dominant. This, in turn, results in underactive gluteals and hamstrings. As a result, patella (knee) pain can occur alongside iliotibial femoral band (ITB) pain and tightness. This, in turn, can create a cascading effect on the lower back, shoulders, arms and neck.

Juxtaposing a mid-foot cleat position to an Olympic squat where the majority of the force to lift the weight is generated by largest muscles known as the gluteals, typically results from the force produced from the posterior of the human body.

Essentially, when force is applied through the heels to ‘lift’ the weight, the gluteals provide the majority of the effort, alongside their quadriceps and hamstrings. To better understand this concept, recall the actions that occur in daily life, such as lifting a box or a child off the floor.

Did you perform the lifting action whilst standing on your toes, or with a flat foot?

The most probable answer is, with a flat foot. Why is that?

Well, the most logical reason is that the gluteals are the ‘preferred’ muscle group. As a result, more power can be generated through this position and most importantly, improved muscular endurance.

A mid-foot cleat position is likely to suit riders of all sorts.

However, the disadvantage of the position results in the foot effectively shortening, thus creating a smaller lever arm. In turn, slight power loss can occur during short sprint efforts where the calf musculature lends their explosive properties.

In most cases, however, the advantages outweigh disadvantages.

For example, during steady efforts such as time trials, the stability of the foot and conservation of energy is central to performance. Secondly, as the onset of fatigue set in, the stability of the foot is improved as less energy and control of the calf musculature is required to stabilise the foot over the pedal.

Practical Implications

Now, through your basic understanding of how the body interacts with the bike, positional trial and error is often the key to achieving the optimal cleat position – whether you visit a bike fitter or through simple experimentation at home.

The beauty of bike fitting is that there is ‘no right or wrong’ in the correct set-up, while the ideal set-up requires the ability to acknowledge your fitness, strength, flexibility and riding goals.

Observing the movement of the knees in relation to the pedals whilst you are riding can assist in choosing the correct spindle length. This would involve the knees tracking directly over ankles during the pedal stroke.

Opting for the ‘Yellow’ cleat reduces the likelihood of injury. If you are a sprinter, provided that your cleat position is perfect, less float can allow for sprint efforts without the fear that the cleat will detach from the pedal.

If you are a larger and muscular rider with a physique built towards fast, powerful and competitive cycling such a criterium ‘crit’ riding, adopting a forefoot cleat position can allow for instant and explosive bouts. While, if your physique is relatively petite and you enjoy endurance and hill-climbing, the midfoot cleat position can provide improved endurance and comfort.

So, what type of rider are you?

Fantastic article thank you! Going to get a bike fitter

I’m really enjoying the theme/design of your weblog.

Do you ever run into any internet browser compatibility problems?

A couple of my blog audience have complained about my website not operating correctly in Explorer but looks great in Firefox.

Do you have any recommendations to help fix this problem?

A comfortable position can vary from each person. But to have a reasonable position, the middle of the cleat should be right under the balls of your feet.

Cyclists to be able to output their maximum power with cleats because flat pedaling over 80 rpm becomes inefficient due to slippage.